On a trip to Georgia and Alabama this week, Director of Development Keith Barrett '80 and I took a dogleg route from Atlanta to Birmingham, though the city of Montgomery, Alabama. We stopped to visit Danny Loehr ‘09, who currently works for the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) founded by Bryan Stevenson. EJI seeks to “end mass incarceration and excessive punishment, challenge inhumane and violent prison conditions, and confront the history of racial inequality and injustice in America.”

EJI sits in a state capital with a troubling past: slaves were taken from the river landing, marched up Commerce Street, housed in warehouses (one of which is the site for EJI) then marched up to be sold on market days along with livestock and produce. Montgomery is the city where Rosa Parks took her stand on December 1st, 1955, sparking a bus boycott and protests until the Supreme Court ordered the integration of public transportation a year later. EJI sits with its mission in the heart of a city with a tangled history. Not an easy history. Danny, who has been working for EJI as an attorney, walked us through the downtown and shared the work he is doing in prisons and with paroled prisoners. We walked up from EJI offices to the National Monument for Peace and Justice, the first national monument to acknowledge the victims of lynching. Late Wednesday afternoon, on a day that was sunny, warm and nearly perfect, we walked into a dark corner of history.

There have been efforts this week to support our students in the unsettling aftermath of the racially motivated killings in Pittsburgh last weekend. How to come to terms with the hate and violence? How to support the victims? What small steps can we take to help mend a present so fractured to create a future that is more hopeful and whole? How do we get to see the other, come to know the other, honor the other instead of building up walls in a time when walls are celebrated and talked about as solutions instead of a trellis for misunderstanding and misguided anger to climb. Could this darkness of our past once again become visible? Is it becoming visible? It was a timely visit to Montgomery.

Walk the battlefields of Gettysburg and it changes you. The room full of shoes in the Holocaust museum in Washington D.C., with the palpable hatred and misunderstanding tangling with the laces, will haunt. How could it be otherwise? And such was my experience on Wednesday when I came face to face with the legacy of lynching and racial injustice that is a part of this country. Of course I knew of the legacy, but emotionally coming to terms with it? That happened two days ago.

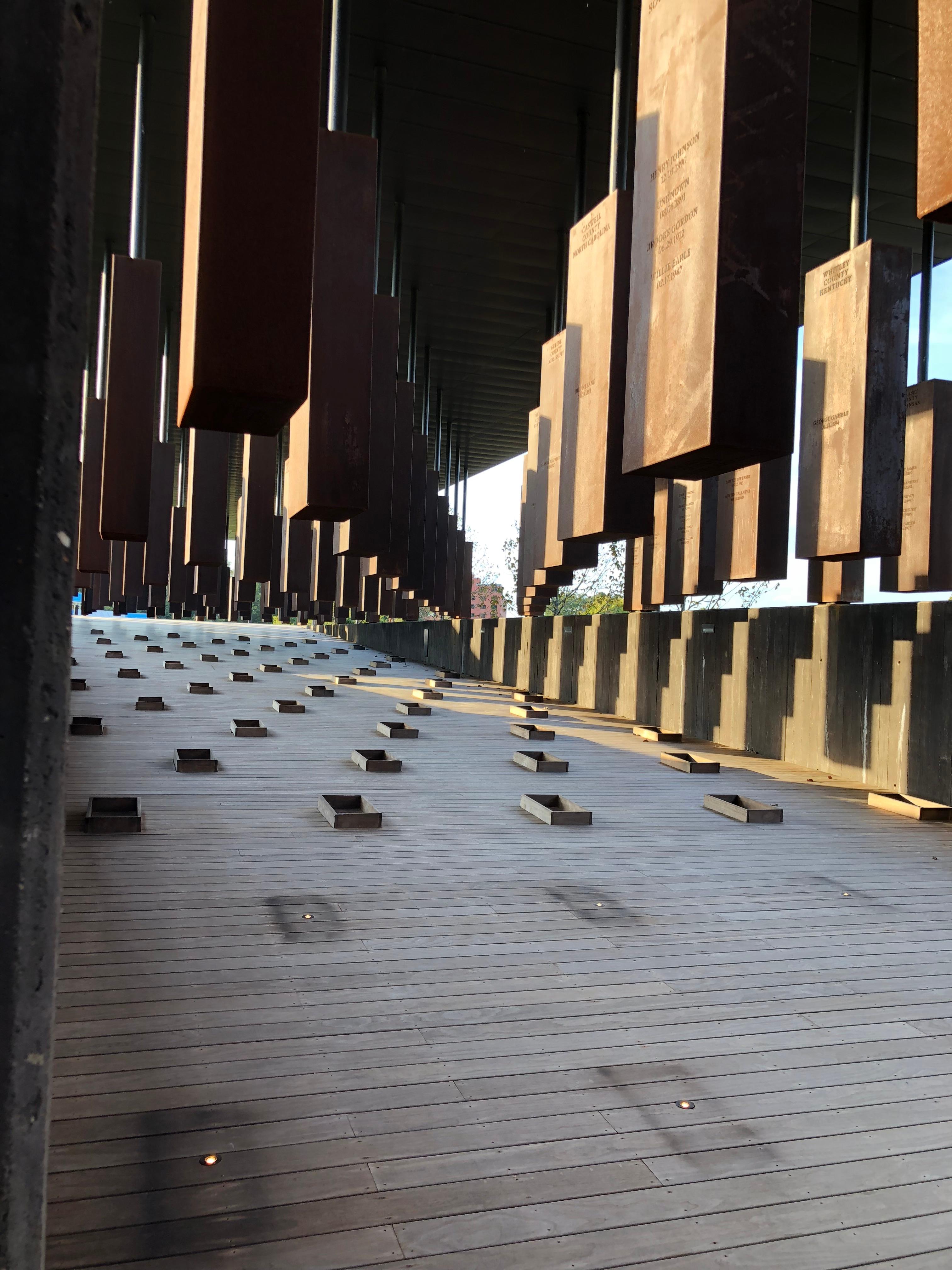

Danny Loehr and Bryan Cleare walked us through the first national monument in this country to acknowledge this violent history. It’s uncomfortable. It’s stark and jarring. It makes you want to weep, and many do. EJI has researched and documented more than 4,400 lynchings in this country, and each one is represented in the monument. Every county in all states where there was a documentable lynching has its own monument suspended from an open air ceiling, and on that coffin-like metal box, rusting and stained, are names and dates. You start walking through the hanging rectangular metal at eye level, but gradually the floor drops away and you are walking under them, under the names, under the victims: Boon 06.28.1877; Martin 06.28.1877; General Duckett 03.21.1899; Isaac Simmons 03.26.1944; Eugene Bells 08.25.1945. Over 4,400 hundred names suspended in the air.

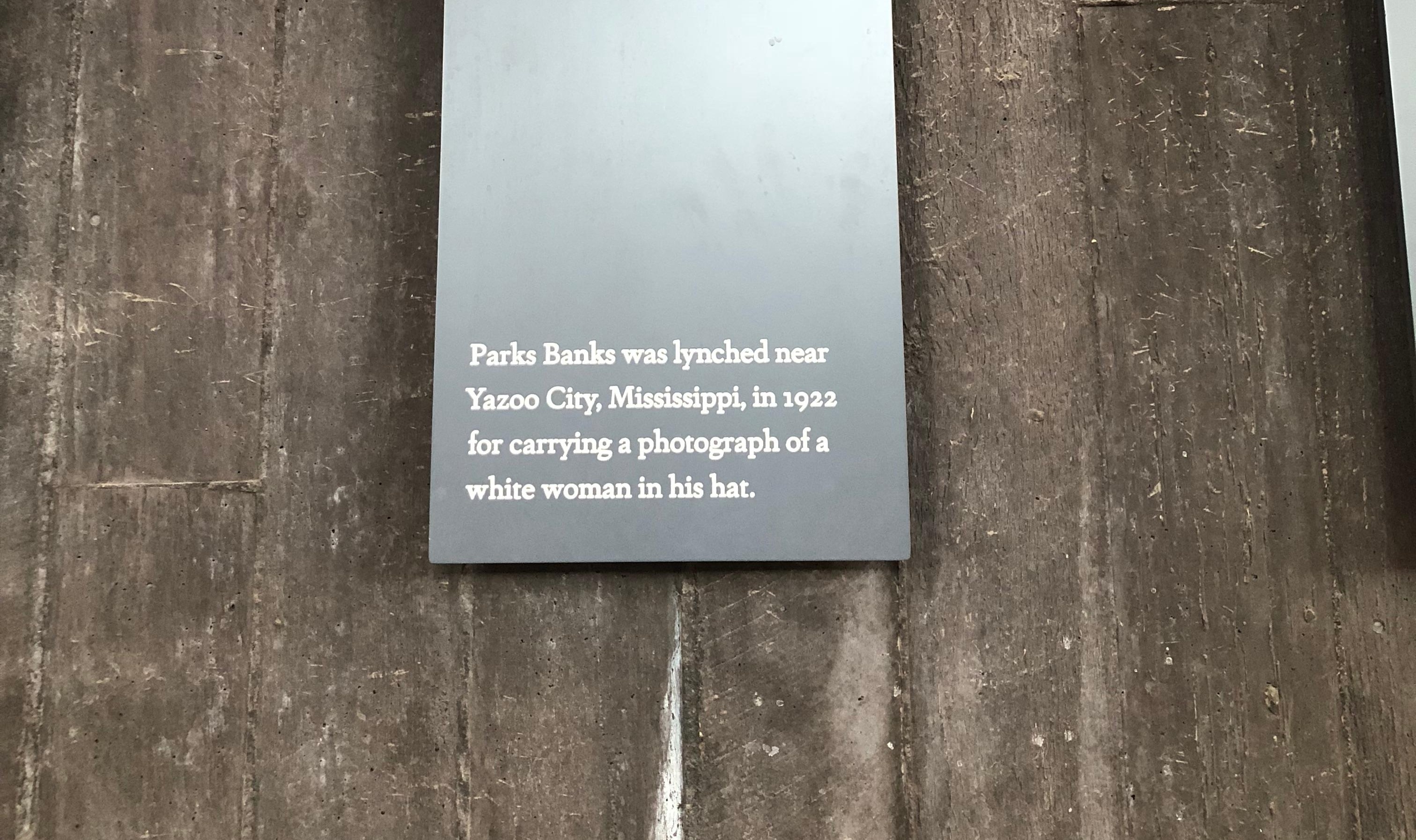

Deeper into the memorial, compounding truth’s discomfort, some of the rationale for the lynchings are on display: after an overcoat went missing in a hotel in Tifton, Georgia, in 1900, two black men were lynched, whipped to death while being “interrogated” in the woods; Park Banks was lynched near Yazoo City, Mississippi, in 1922 for carrying a photograph of a white woman in his hat; Private James Neely was lynched in Hampton, Georgia, in 1898 after complaining when a white store owner refused to serve him. There are accounts of burnings, children being lynched, a pregnant woman lynched, lynchings as “entertainment” in front of thousands of spectators. How flimsy, cowardly, and pathetic these reasons seemed, but there they were, stark and startling.

What does reconciling with such a history mean? It runs a gamut, but in talking with Danny about his work and the memorial, we discussed the power of simple acknowledgement. Those responsible for lynchings may not be us, but it is a part of our collective history, woven into this nation’s DNA and we need to own that history. All of us. By owning it and promising not to forget, we build a bulwark against intolerance, against the hate that made slavery and lynchings possible, and the hate that still lurks in distant and not so distant corners waiting to climb the trellis we give it, waiting to bear the fruit of violence we see playing out today. This ownership is an important step, and it is not just some who should own; we all can and must carry knowledge forward even if it rubs uncomfortably.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice dips down, and just before turning the final corner these words are etched on the wall:

For The Hanged And The Beaten

For the Shot, Drowned, And Burned

For The Tortured, Tormented, And Terrorized

For Those Abandoned By The Rule of Law

We Will Remember

With Hope Because Hopelessness Is The Enemy of Justice

With Courage Because Peace Requires Bravery

With Persistence Because Justice Is A Constant Struggle

With Faith Because We Shall Overcome

It’s not an easy fix, but facing history and accepting our shared past is a good step in the necessary direction we must take.

Mike Henriques P'11, P'15

Proctor Academy Head of School