This week's Mountain Classroom blog post is a "read one get one free special"! Mountain Classroom was treated to a glorious 3-day backpacking trip in Grand Canyon National Park in the final days of March. We started our hike at Hermit's Rest Trailhead and made our way down to the Colorado River at Hermit Rapids. There we rested for a layover day before returning to the South Rim on the same trail. Before and after hiking, we camped at Mather Campground in the park at over 7000 feet where we experienced snow flurries and a herd of curious and rambunctious elk.

Cassie ’16:

Have you ever seen a group of high schoolers become blatantly giddy over hearing the sound of rushing rapids? What about of a group of high schoolers so excited to go for a swim that they can't hold back the giggles? These are some of the many gratifying experiences that our backpacking trip to the Grand Canyon provided us. Every angle held a view worth getting excited about and every member of our group witnessed a view they couldn't ignore. However, the most memorable and meaningful group experience that we shared was our creation of a community living contract. We spent hours debating what our core values should be, how we should design our group flag, and, perfectly wording our community living contract so it rhymed to each of our likings. Faith, Truthfulness, Respect, Integrity, Bravery, and, Empathy ended up being our community's core values (after much passionate debate). With this conclusion it seemed only right to name ourselves the F TRIBE in order to fully commit to and embody our newly established community principles. Our finalized community living agreement is as follows:

We the F Tribe these values we strive

to uphold and live by.

Before we speak we think: Is this kind? truthful? constructive?

Our disagreement will never be destructive.

We'll be positive and keep spirits high,

because a good mindset is the only way to get by.

We're as open as a book because it keeps us together,

Immature jokes could go on forever.

Conscientiously acting with intentions that are true,

bearing kindness in mind we'll stay as a crew.

We respect people's thoughts and space,

together we make a judgement free place.

Faith in equipment, faith in each other,

enough trust between us like sister and brother.

The truth we will honor we'll never deceive,

and responsibility we will give and receive.

Integrity is the glue that keeps us strong,

even with no on watching, we know right from wrong.

It's not the absence of fear but the strength not to quit,

in order to be brave you just have to commit.

To bridge the gap between points of view,

we must be empathetic, through and through.

- Spring Mountain 2016

All in all, I can confidently say that aside from the unfortunate encounter between my behind and a cactus, we had an awesome experience growing closer as a community with the privilege of doing so in an incredible environment.

Maggie ’16:

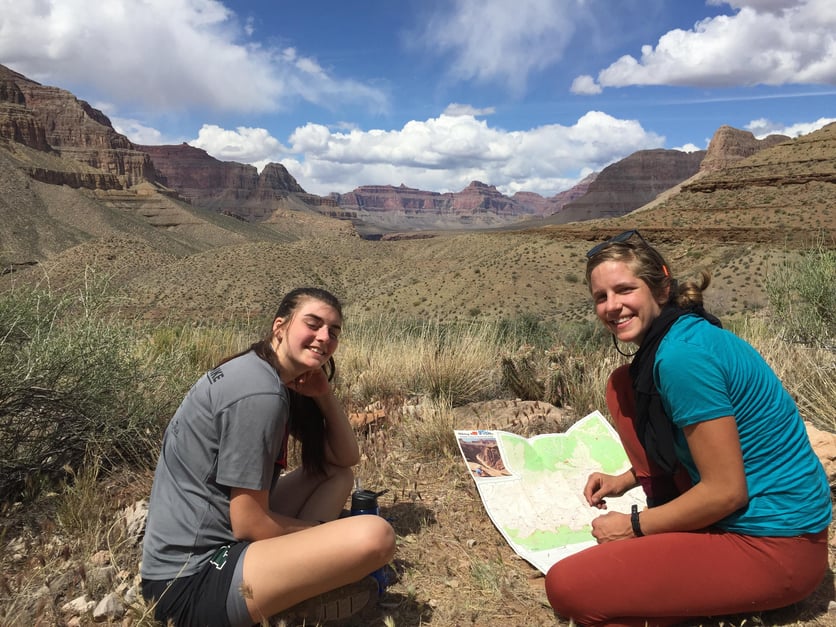

One of the greatest moments of our backcountry trip in the Grand Canyon happened just 10 minutes after we got on the trail. In turning the first corner we all made the same "awe" noise and stood with our mouths wide open. We were looking out over the Grand Canyon as the sun was just coming up. The way the sun reflected off the canyon was breathtaking. Our 7 hour and 15 minute hike down was full of amazing views. Not until halfway though our hike could we actually see the Colorado River. We soon came to realize that this place was so much bigger that it first appeared.

The Grand Canyon is striped with different colored rocks that tell the history of the landscape. The bottom was covered with rocks of all the places we had been. Colors ranged from red clay to light green to deep purple and everything in between. They created a rainbow colored walkway for the last mile to our campsite. At 3 o'clock we arrived at our camp, which was a beach next to the Colorado River. We spent a day at the bottom of the canyon recharging for our hike back up.

Hiking up the Grand Canyon was probably the hardest thing I have ever done, but it was so worth it. When we got to the top we saw tourists with iPhones looking out over the top of the Canyon. They came all this way to stand at the top and take pictures. I wish they could have seen the canyon from all the angles that we had. They did not get to see and hear the rushing Colorado River. They did not get to look up at they canyon from the inside or see it at sunrise. They did not get to sleep by the river and look up at the thousands of stars. We worked for those moments. We got up early and hiked 17 miles and 9 thousand feet of elevation in total. The hard work we put in made our experience in the Grand Canyon that much more rewarding.

Following our trip to the Grand Canyon, our group arrived in Boulder, Utah in early April for a week of adventures. We set up a basecamp on David Holladay's beautiful property where we prepared for a minimalist backpacking adventure for three days. The time was spent acquiring skills in friction fire, making cordage (rope from plant fiber), and building shelters, duff beds, and cattail sleeping pads. Our hope was to glimpse the experience our ancestors had during the Stone Age in order to have a foundation for the rest of our term-long studies in food systems. We wanted to start where all humans began--hunting and gathering.

Katie ’17:

This past week, Mountain Classroom worked closely with David Holladay, a giant in the world of primitive living skills, to prepare for and execute a three-day trip in Utah’s Circle Cliffs. This backcountry trip would be exceptional because there would be no backpacks, no tents and no sleeping bags. We planned to venture out carrying less gear than ever before in pursuit of simulating a fraction of the hunter-gatherer experience of our ancestors. We arrived at David's property where we would be camping for 3 days preparing for the trip, and soon we were thrust into acquiring the most important skill we would take with us into the Circle Cliffs. We had to learn to make fire.

At David's, there were no matches and no newspaper to receive an eager flame. We began as a group by making fire the hardest and most primitive way possible, with the fire plow; essentially rubbing two sticks together. We had a dry log and a short round stick sharpened to a point. This technique mandated that the shorter stick be vigorously scraped along a groove in the log until smoke began wafting up from the log and eventually an ember was born. We began with one person starting off with a high tempo, making as much progress as they could before someone else dropped next to them, grabbed the stick with them and matched the pace. Then the starter could peel away and allow the next person to continue the job. The stick never stopped moving between transitions and the work done by the person ahead in line was not lost as the next person began. We formed a line and cycled through the group growing wildly excited as black ash began piling up along the groove (a sign that good friction was being achieved) and smoke appeared. We cheered as each individual dropped down to the log and furiously scrapped away until, panting and arms limp, they handed the stick off. We knew we were growing close and finally Timbah took the stick and his arms whipped back and forth like pistons, churning up ash and producing more smoke. Suddenly, David called out and bent over the log scanning the pile of deep black wood shavings. The whole group leaned in straining to see what David saw. Even though nobody labored over the log, a tiny curl of smoke glided lazily from the ash. David blew gently, and a tiny, barely perceptible red speck glowed. We had an ember.

Contrary to the image in my mind before actually trying friction fire, a flame does not majestically burst from the hole bored by the wood. Rather, if everything works perfectly (as it rarely does), aspiring fire makers will produce a minuscule ember as susceptible and delicate as a newborn baby. The ember must then be carefully cared for, too hard of a breath could put it out while too little air would suffocate it. After letting the ember grow and consume the bed of wood shavings around it, the time came to transfer it into the nest, a soft bed of fine bark wisps and grasses. All eyes trained on Allie's hands as she and David nudged the ember into the nest. The ember slipped into the depression made in the nest for it before Allie's hands clamped around the nest grasping it, as we had been instructed, like a hamburger.

Coco, Allie and Cassie surrounded the nest and began blowing ensuring the ember would have enough oxygen as it came in contact with all sides of the nest and began to spread its slow burn. Thick grey smoke dribbled from all sides of the porous nest as the ember grew and suddenly an elusive orange streak darted up. Flames began to consume the nest and it was deposited into the sand. Students scampered and collected twigs and dead leaves to add to the fire as the flames grew and swarmed hungrily. Before long sticks and small branches were in the mix and David spoke up. He had explained earlier that perfection is easy to achieve with making fire. His logic is that if you make a fire, no matter the kind of wood used or the time it takes, you have made a perfect fire. Success is perfection. Now David elaborated on what this success meant. David said that fire making was not an individual success story, if one person is able to make fire, then the group is able to make fire. After making fire as a group, we split up and struggled for hours with the relatively advanced technology of a bow and spindle to make fire on our own. It was a bit competitive, with everyone peering around every so often to see if someone had yet managed to eek out an ember, but David's words hung in the air. If one of us was able to make fire, it wasn't a personal accomplishment, it would mean that the group would have fire, that we would be warm during the chilly Utah nights. As we pained over our individual fire kits, frustrated by loosening bow strings and tired arms, I like to think that rather than racing each other, we labored all day because we sought to achieve fire for each other.

Allie ’16:

Day two in the Circle Cliff’s backcountry brought a day of adversity and adventure. We woke with the sun and filled ourselves with blue cornmeal soup, cooked by the fire. Some of us were rested after finding comfort in leaf piles and grass mat blankets. Others were groggy and dusted with ash from a long night cuddled around the fire and eager to see the sunrise. After our breakfast, we set off on the trail, first winding our way through the bottom of a canyon. We started the second day much like the first, in silence. Without talking one is left with the company of their own brain and the sights they see. At times I was completely in my head only looking two feet in front of me, but then I would look up and slide into the present noticing the biscuit root tops, the elk paths and the red rock cliffs striped with sandstone. I pictured myself as an elk picking my way through the juniper and pinyon pine trees, taking long strides through the sagebrush meadows in search of water. I chuckled at the parallel between my life in that moment and that of the elk.

Our mission for this walk was simple. We needed to get to the next campsite where there was water and food. I was carrying just enough to keep me warm at night. I felt free compared to the usual amount of things I carry into the backcountry. In a society where we use sidewalks, paths and trails we rarely get to physically choose our own. In contrast, I was deciding which rocks to step on and the route I took around bushes. David Holladay’s mission for us was to connect with our surroundings and understand the lives of the people before us.

An elk’s life is not much different from the life of their great-great-great-great grandfather, mine on the other hand is. There are new social norms and technological boundaries being broken everyday. With that said, my human needs have stayed the same. So, as I walked and tried to take in all the views and the sounds, I think I felt a bit of the connection David had hoped I would. My stomach was empty and my body was fatigued, but the breeze pushed me and the red cliffs pulled me and I kept choosing my trail.