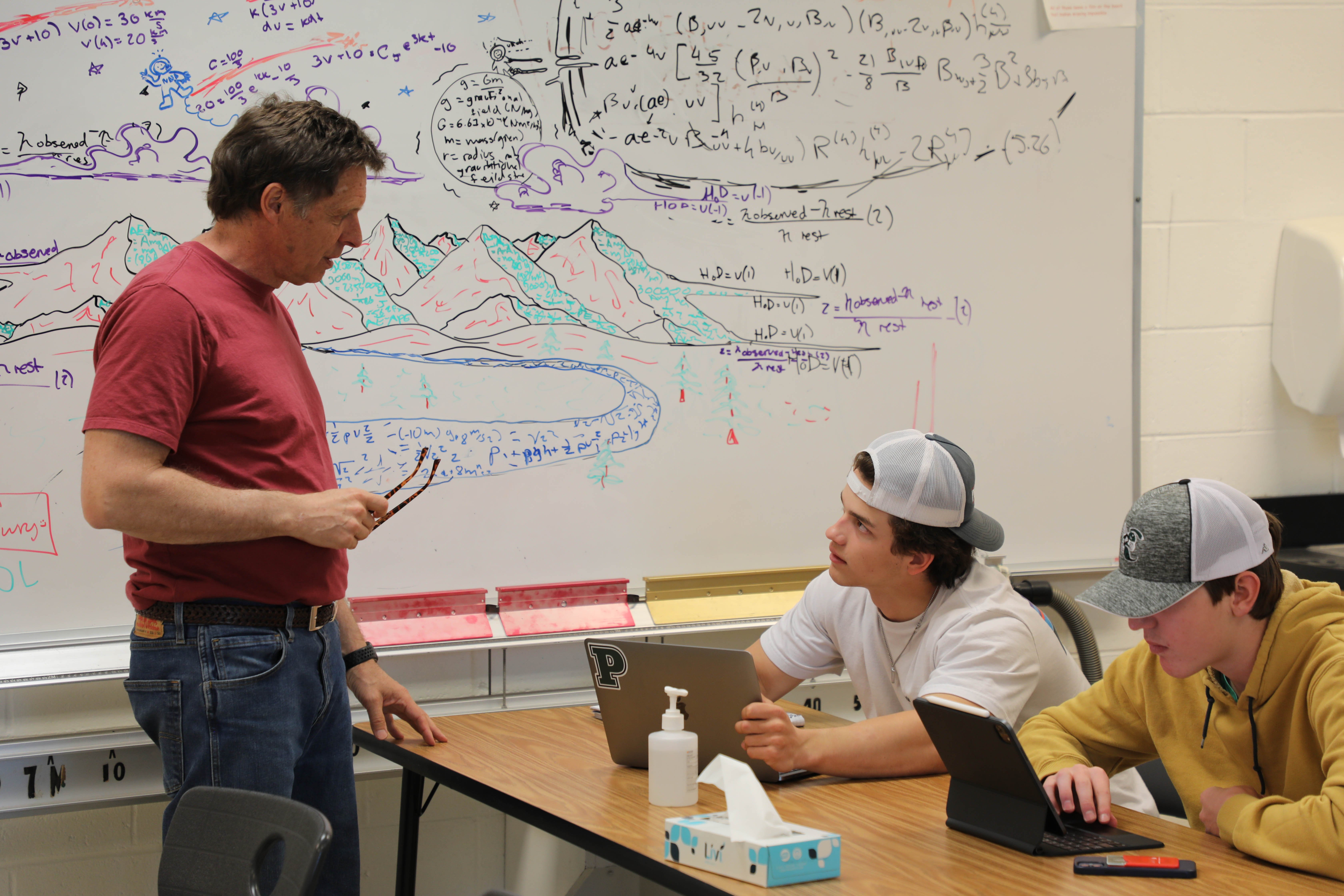

At the beginning of last spring, I had the opportunity to observe Tom Morgan’s Creative Nonfiction class in action as students worked in small groups to create podcasts. Their assignment was to document the collective Proctor response to the first weeks of the war between Russia and Ukraine. Tom invited me to his class to discuss the basics of digital storytelling and audio sequencing, including how to select, trim and arrange different audio elements into a cohesive story.

I was surprised to discover that students had already immersed themselves in the editing process and, through trial and error, online research, and collaboration with classmates, had “first drafts.” They asked excellent questions, eager to expand their growing knowledge of how to tell a compelling story in podcast format and the nuts and bolts of creating a podcast from the ground up. They referenced, some with a grimace, the many hours spent listening to and trimming audio clips in search of the perfect sound bite to support their story or elicit an emotion. These students, all with no previous podcasting experience, were creating professional and polished audio collages documenting a moment in time on Proctor’s campus (and in the history of western Europe).

To a casual observer, this may have seemed like any other group project, albeit a class project that utilized a popular format. When I returned one week later to listen to the final products, however, I began to realize that what I was witnessing in this English class was a microcosm of Proctor’s educational model at large.

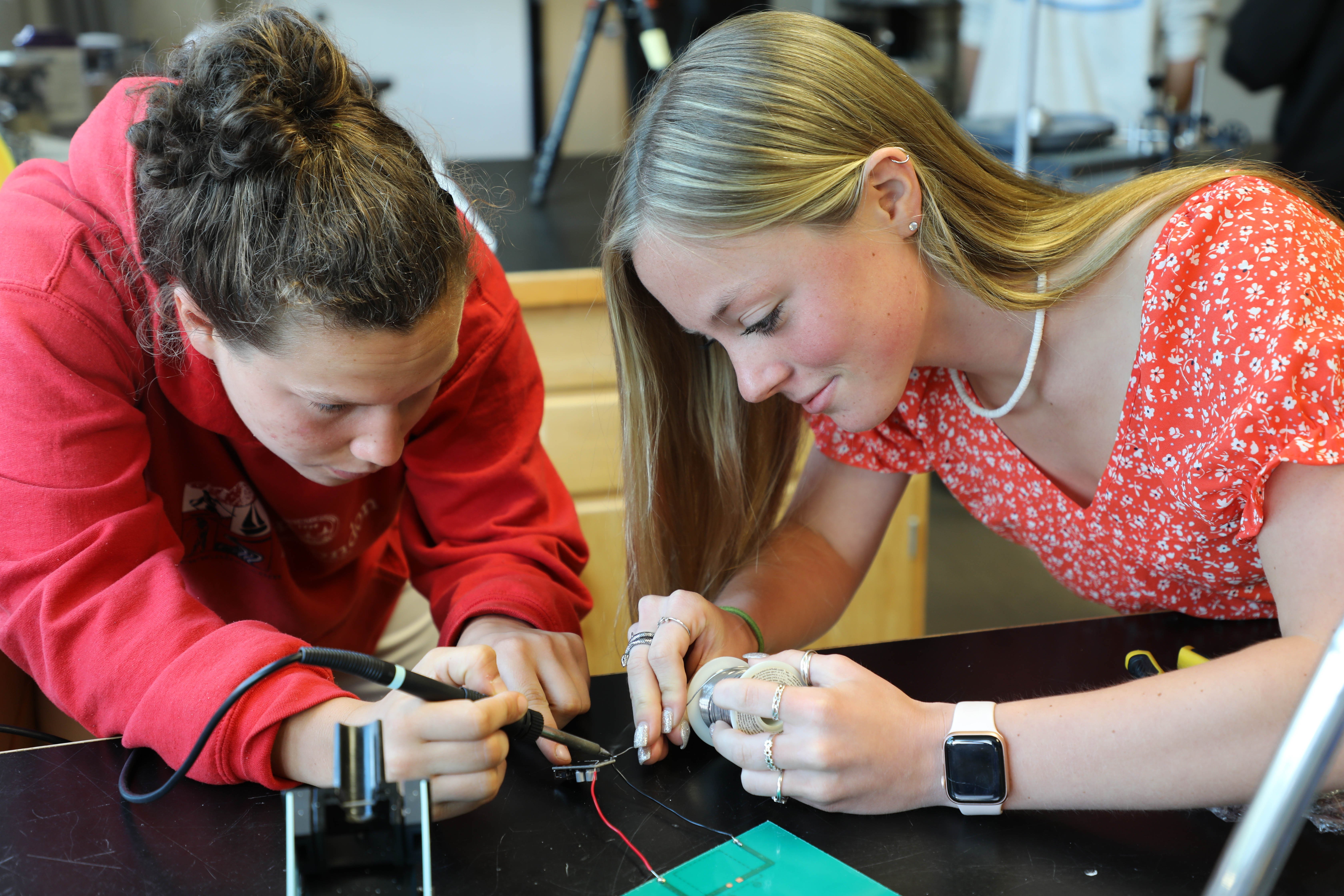

At Proctor, experiential learning occurs not only during off-campus programs like Ocean Classroom, where students learn the skills to operate a 130-foot schooner, but also here in Andover. It is put into practice both by students practicing painting techniques en plein air in southern France and by studio art students painting still life scenes in Slocumb Hall. Proctor’s 2500-acre campus and community members serve as a constant living laboratory for learning.

These English students did not have to go it alone. They had guidance in the form of a detailed assignment description, with “scaffolded” homework assignments, podcast examples and tips, and a grading rubric they had created as a class. More importantly, they had access to a teacher (Tom) with experience creating podcasts, who served as a safety net and sounding board.

The students, however, did the work, pounding the pavement to find interview subjects and recording interviews, watching GarageBand tutorials, and working in small groups to arrange and order audio clips. They were given a framework but it was up to them to fill in all of the blanks; the overall direction and end result of their project was entirely in their control. They built real-world technical skills while applying previously learned creative nonfiction techniques (existing neural networks) to a new medium, thereby acquiring new knowledge and forming new connections.

Finally, students were pushed out of their comfort zones as they asked difficult questions and were confronted with opinions about the war in Ukraine that were, in some cases, very different from their own. As students worked to synthesize these differing opinions and process fast-moving events across the Atlantic, many were motivated to read and learn more about the root causes of the conflict and the history of the region. A sparked interest in a new subject matter or seeking to understand an issue from a different perspective are also critical elements of Proctor’s educational model, which aims to graduate life-long learners and thoughtful contributors to their communities.