Today’s offering for The Journey comes through the voices of John Around Him and Lori Patriaca ‘01, both of whom have served a critical role in helping our Proctor community connect with, understand, and become a part of the Lakota communities of South Dakota, continuing a legacy of connection first made by John’s father, John Around Him, and late faculty member George Emeny in the 1980s. John spent last week visiting classes, spending time with students and faculty, and immersing himself in all that is Proctor. Enjoy John and Lori’s offering below.

John Around Him:

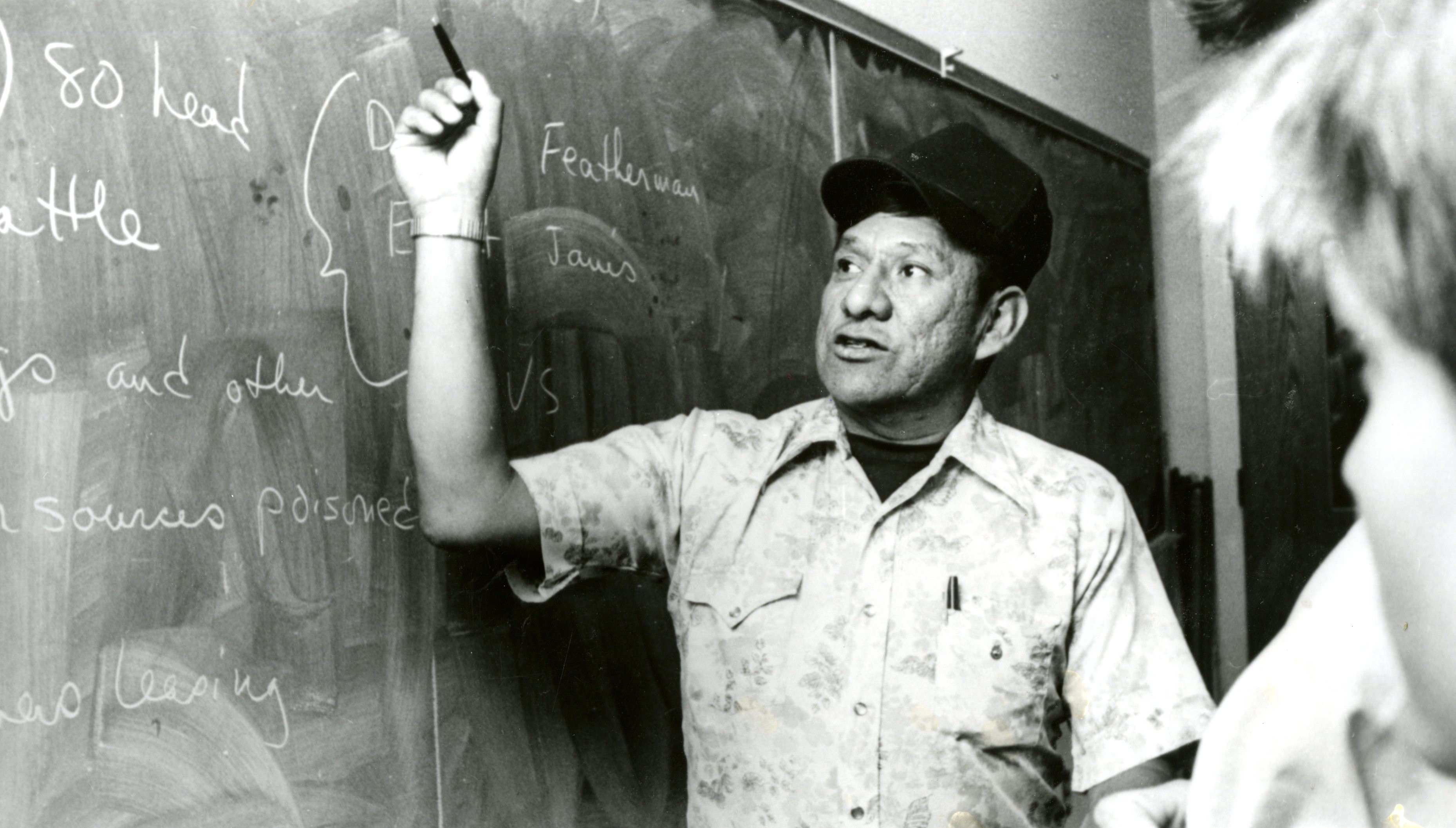

This year marks my seventh year as a visiting educator at Proctor, but my connection to this campus reaches back much further. My first visit to Proctor was in the 1980s when my father, John Around Him Sr., and my godfather, Albert White Hat, decided to journey to Andover, NH to address the Native history that is often inaccurate or absent in western textbooks. Walking around campus, I felt remarkably at home. I can find my way around campus reasonably well. Meet you at Maxwell? I can do that. Meet you at Elbow Pond? I can do that. Meet you at the dining commons? I can definitely do that too. What never gets old is seeing the courage among students as we discuss the difficult past between Native peoples and the U.S. Tom Morgan and I often refer to this as courageous conversations.

Lori Patriacca ‘01:

Almost seven years ago, I walked across an open field on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and shook hands with John Around Him. He was hosting our small group from Proctor Academy for a tour of the reservation, the Oglala Lakota College, and his family's home. As he pointed out details, told stories of his family's deep connection to Proctor, and explained a little of the Lakota belief system it occurred to me that this man was a natural teacher. Then I found out he was a ninth-grade English teacher in Baltimore. Something sparked. Wheels started turning. We promised to be in touch.

Here we are, all these years later and John has officially been in a classroom with seven years worth of students. He has collaborated with US History teachers, Language teachers, American Literature teachers, and the Culture and Conflict course. He has worked with our ninth graders in their classrooms and recently, on the trail to the Proctor Cabin. He has worked with our seniors in AP Language as they grappled with Ta-nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. When faculty hear he is coming, they scramble to get into his itinerary, the students light up and exclaim, “Oh, I love John! I remember him from Sophomore year!”.

All of this makes me simultaneously proud and filled with gratitude. John is carrying on his father’s legacy and he is bringing his lived experience and perspective into Proctor’s classroom discussions around our country's history, the American Dream, and the confluence of race, culture, and language. I will never be able to thank him enough for his time, energy, and devotion to sharing his knowledge.

Why does this matter? Why does Proctor make sure to coordinate a visit every fall (and sometimes in the spring, too!)? Because we want to do more than read books. We want to connect students to the land, to one another, and to a fuller understanding of history and its legacy.

This year John was on campus for Proctor’s celebration of Indigenous People’s Day. We call it a celebration though some of the content is devastating. The Culture and Conflict course shared letters with the community detailing the fight for clean water, raising awareness of abuse against native women that goes unrecognized and unpunished, and calling into question the dominant culture and its disconnect with the land and its first stewards.

JAH:

I spoke with the community about the impact of federally-funded Indian Boarding Schools. Hundreds of Indian Boarding Schools, which spanned the U.S. and Canada, were built during the 19th and 20th centuries. Children were forcibly taken from their homes, forbidden from speaking their language, and made to cut their hair to name a few. The overall goal was to dismantle Native languages and cultures. These schools were nothing like what we experience at Proctor today. This summer, the discovery of thousands of unmarked graves, mostly children, at former Indian Boarding School sites across the U.S. and Canada, made an already tragic story that much more heartbreaking. These stories must be told. Though they are not the only ones.

I love the English department’s theme this year, which is the danger of the single story. Indian Boarding Schools, although tragic, are often presented as a single story, but there is so much more to Native communities and our country. For Native people, other stories include our ability to cope with calamity through friendship, forgiveness, and fun. While no one person or school is perfect, Proctor Academy is leading the way by avoiding the danger of the single story.

In Lakota thought and philosophy, we are taught that as humans we can be amazingly destructive. We are also taught that it is within our power to come together as relatives, face our history, and work towards healing.

LP:

At the moment fifteen out of fifty states celebrate Indigenous People’s Day rather than Columbus Day, including our neighbors Vermont and Maine. In New Hampshire, seven out of two hundred and thirty four cities and towns have adopted this day though at the state-wide level this has not gained traction. On November 8, Proctor students will have the chance to attend a public hearing with the Concord City Councilors to support the city in replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous People’s Day. At Proctor we adopted Indigenous People’s Day because the reality is the world on Turtle Island existed long before Columbus turned up with his fleet of ships and Columbus never stepped foot in North America. To claim him as a National Hero deserving of a holiday is a stretch at best.

We recognize the importance of lifting up our land’s original inhabitants, rather than the individual whose actions resulted in the genocide or enslavement of multiple civilizations to our nation’s south. Recently, there has been a movement in some states to ban teaching indigenous history in public schools. The need to recognize Indigenous People’s Day and dismantle the false narrative around Columbus is increasingly urgent.

We will not be silent and passively allow Columbus Day to persist when there is a clear alternative. On the next Indigenous People’s Day take the time to pause and honor those that came before us and those whose ancestors survived the genocide of their people and cultures. Our next step is to assist New Hampshire in recognizing mistakes, accepting change, and healing together. In the year 2000, New Hampshire became the last state to recognize Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. We hope to be a leader in winning the official recognition of Indigenous People’s Day.

JAH:

As I journey home, I want to say thank you to the Native American Connections Program and Brian Thomas for inviting me, to the teachers for sharing your classrooms, to the students for your courage in having difficult conversations, and to the community for amplifying Native voices. Let’s keep working to achieve this idea of everyone in the world living together as relatives.