“Tank. Tank. Tank." The loud sounds of “tanking, clanking and rattling” of the old steam pipes hissing down in the basement of Maxwell Savage punctures the serenity between the “tick, tap, ticking” of our collective keyboards. Four boys and I are serving early morning mandatory Sunday study hall on a blustery mid-February day.

Some people say that February days and nights are some of the longest of the year. They drag endlessly on, seemingly stretching far and wide into a forgotten recent past and an opaque summer to come, beating against any thoughts that they will ever end. Mandatory Study Halls are those long drudge-y days times ten.

This particular morning, I am thinking hard about discipline at Proctor. As one of the two Administrators on Duty, my co-AOD buddy Annie Mackenzie and I are soldiering through a weekend of being the people who have final say of “no” or “yes” as to whether a student can leave campus by approving (or rejecting) their Orah pass. Our days, especially this one, are like Bill Murray’s “Groundhog Day.”

Often in schools, we think that the years before in our particular school were better and harder, that the kids were easier and smarter, that they learned quicker and faster, that is of course except for some rare souls who were gifted beyond belief. I am here to tell you that that is not the case.

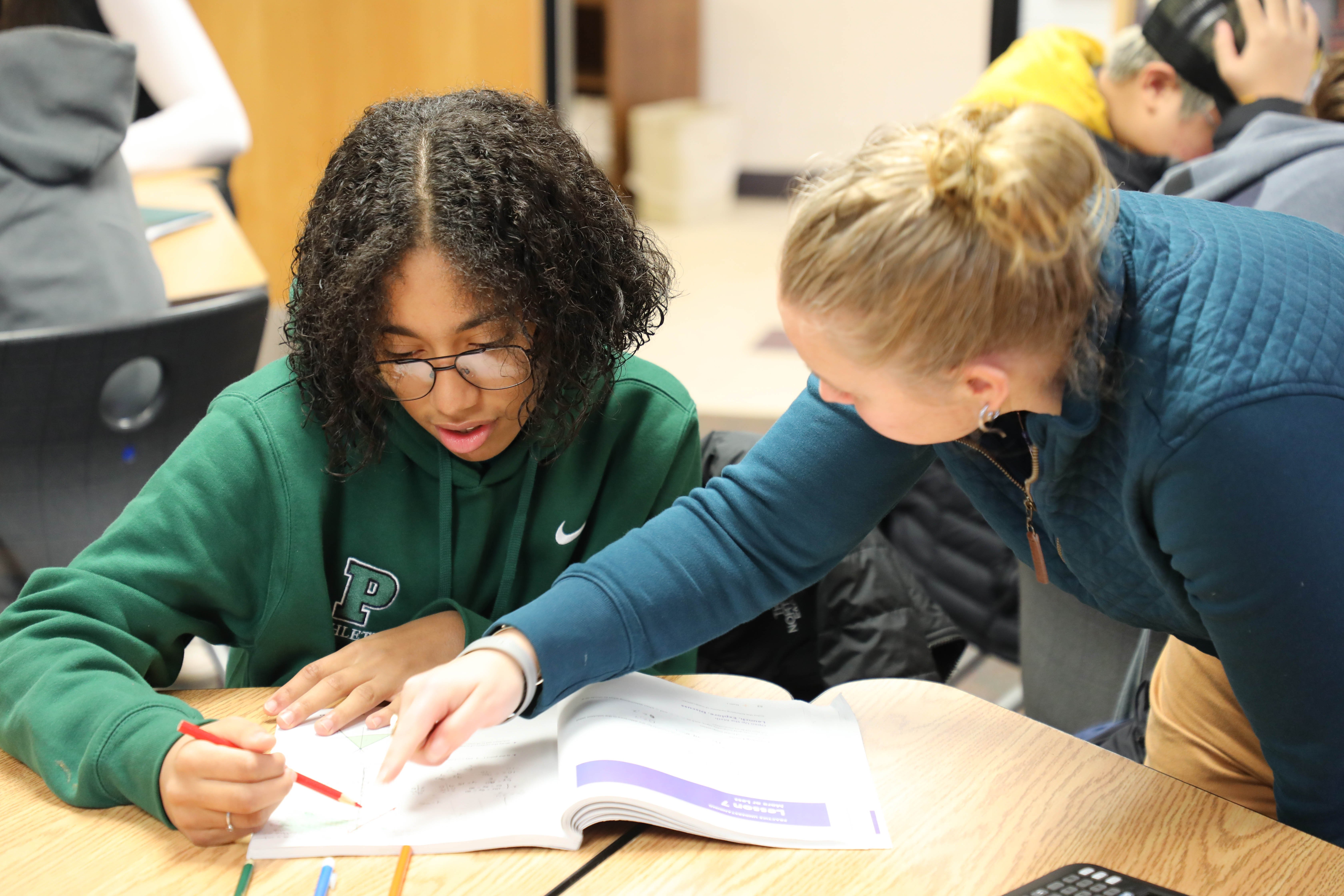

Last evening - Saturday - in the Wise Center, Sarah McIntyre, Proctor Class of 1990, was scouring old yearbook pages of past Proctor students in their neatly donned sweaters and collared shirts, which looked like any other prep school and timeless all at once. Although scrubbed and cable-knitted, they too had to face-off against “the man,” that was Proctor or Chris Norris who was Assistant Head of School at the time. Proctor was 250 students strong during that era. We began this school year (2022-23) with 381 students, and it feels like a different bygone school and era, picture-wise. And, the times, they are a-different.

Some say that students’ needs and characteristics have changed. I’m not so sure about that assessment. By the pictures in the 1991 Green Lantern, we have lurched forward into an even more “relaxed-fit” kind of culture, especially when I look through our own current social media sites or of the sites of the school magazine pages of our peers. Expectations have changed, but I am not certain if students themselves have changed all that much in the past thirty years.

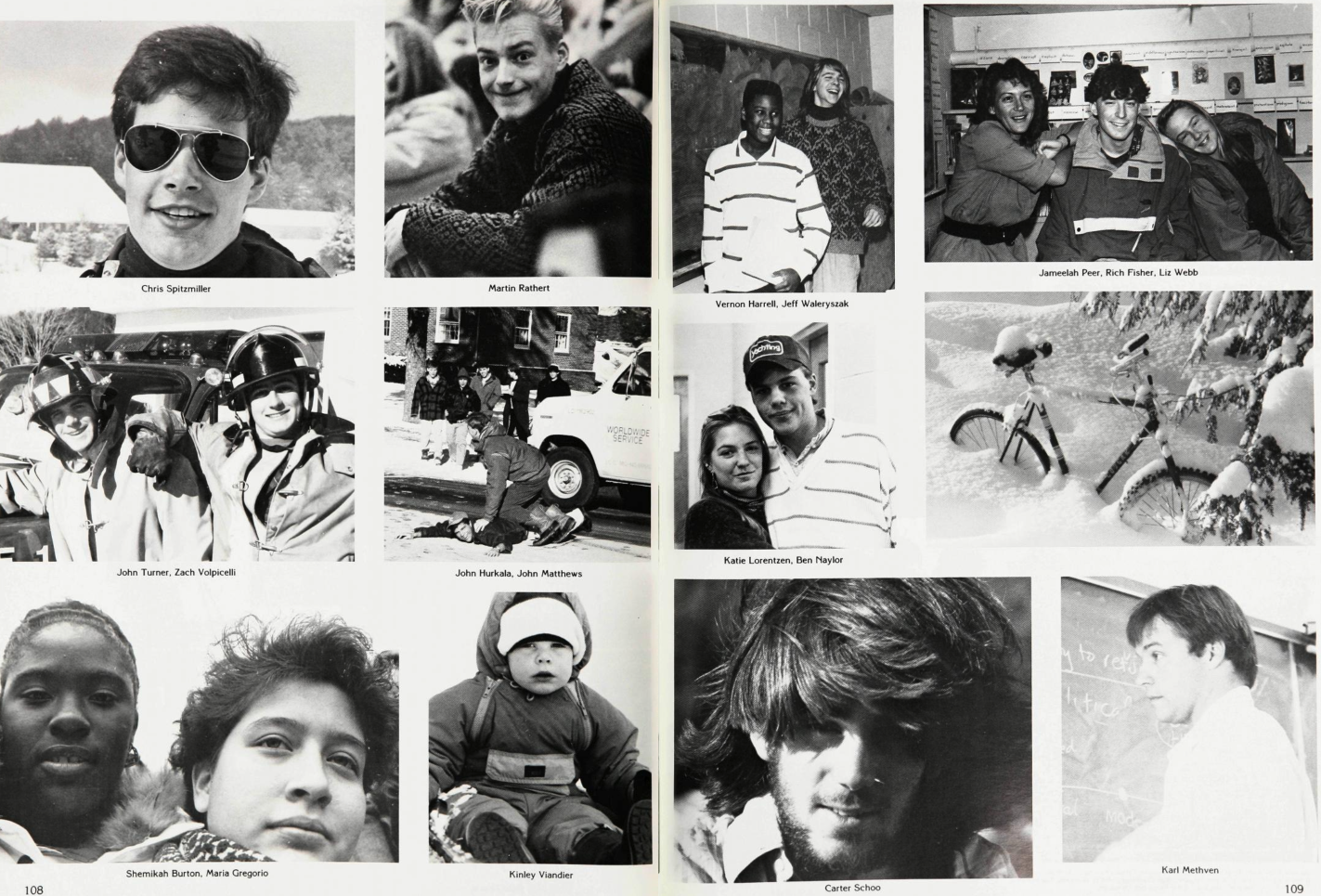

This is all to say, that for the most part, kids are kids. On the whole, when I compare Proctor to other places I have seen or have worked, our students appear to be held in high regard by each other and by their teachers. I overhear and am privy to conversations that today’s teachers have with and about students. They don’t seem any more anxious or stressed than those students from other schools or at other times in my three decades in independent schools. (Note: Social media and the advent of the ubiquitous cell phones have made things different, but more on that later.) Instead, perhaps our expectations of them have changed. In other words, we expect more from them and ourselves since getting into colleges and becoming successful at the next level has never seemed so perilous. Indeed, life itself seems to be fraught, which is what the media tells us. Maybe that’s it, there is just so much more media to juggle. It’s what the philosopher Viktor Frankl says about the individual: “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” But what about the power and growth of the individual within a community? Perhaps this is also our work as adults–parents and educators. Perhaps what we must attenuate is a new kind of way of responding to behaviors – as a community – that seems less out of the norm, out of context, aberrant. That community norms become more sacrosanct and what we explicitly value, which is connecting individuals to community.

So, let me repeat this: Our students’ behaviors and their responses have pretty much stayed the same even as compared to us in different garb from years and years ago. They and we have turned out okay in the end. The individuals must still learn to exist within the framing of a strong community, no matter how people look or dress.

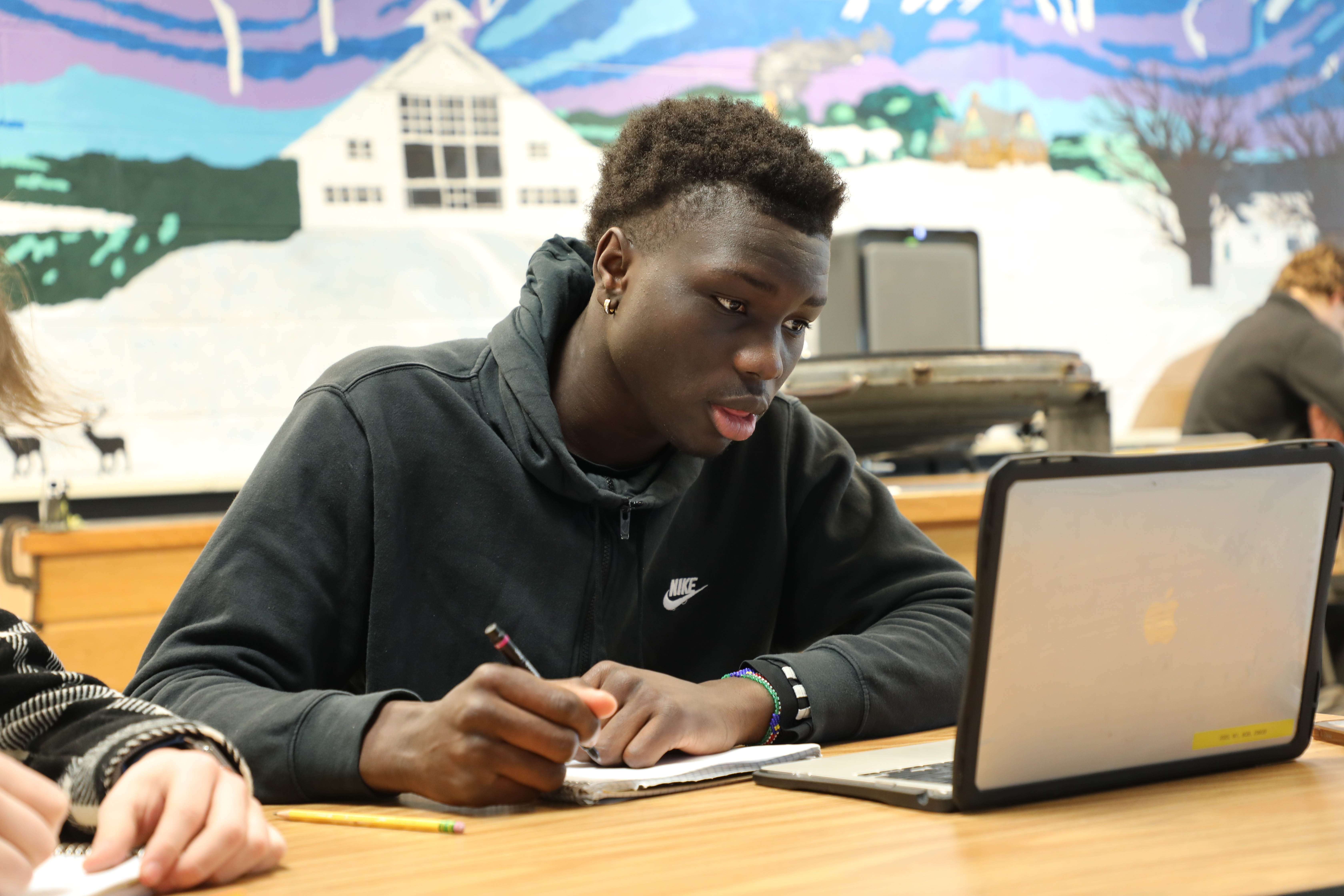

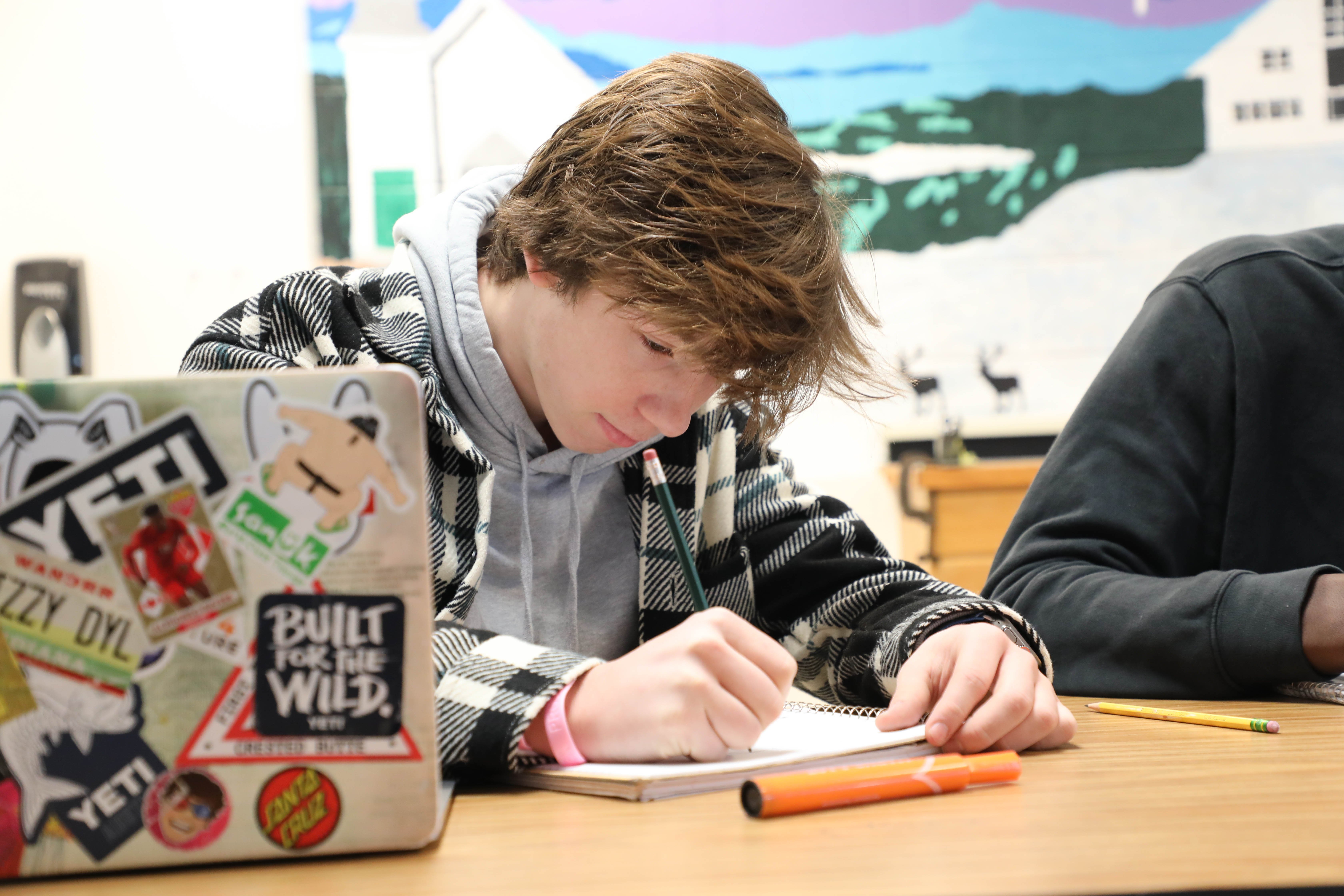

Even when our students' actions feel out of the norm and they are given some sort of restriction as a result of actions beyond the pale, which amounts to sitting with me on a Sunday morning, reading a book or catching up on missed work. Perhaps in the distant 1940s - 60s we would have had them clearing brush on the hill or snow plowing in the back of some lot. (“That’ll teach ‘em!”) But today’s students are not that ilk. They didn’t grow up in the shadows of World War II or even the Cold War. They haven’t just come off the farms or land, most of them. They did grow up in the presence of unprecedented peace and prosperity in our times. (“Thanks, Neville Chamberlain.”) The threats of having to be better than some other external bogeyman, nation-state receded as opposed to many of us older folks who had to duck and cover in case “some axis of evil” decided to drop an atomic bomb while we weren’t watching.

Our students have grown up in a “Peter F. Drucker’s knowledge economy” and world where punishments of fear and loathing are no longer de rigueur. Why put fear into a system of things – like school and schooling – that’s already under assault, making us all anxious of things beyond our control, like climate change and unstoppable viruses that flummox the best of us?

So, what is this all saying?

We have designed a school community that asserts (“understands, values, and connects”) the inherent dignity and worth of “the individual” to the fullness, direction-setting, and significance-making of “the community” with conclusions that are more about natural consequences than Dean of Student-made Calvinistic, crime and punishment scenarios.

And, perhaps this is where we falter a bit? Living free and anxious or dying to know why - in their own mind - a teenager matters is what this age and stage is all about. How do consequences help in this discovery of self? Is this preferable to the hard lessons and installation of a work ethic from days of yore? To be honest, I am not sure. Yet, I have seen time and time again the idea of natural consequences prevail when individuals are connected to a community they LOVE. After all, what’s worse than being excommunicated at some point from what you realize in hindsight as paradise? Perhaps college and getting in is not the goal. Perhaps our goal is trying to perfect our more perfect Proctor union is what we are after. Or, trying to get one day better every day, instead of living in a hazy and halcyon past version of Proctor. Living as an individual within a community does come with some sacrifice of the self–and selfishness.

Our work in terms of discipline, as messy as it is, relies more on reason and thought, as opposed to fear and loathing. I must admit, that is not how many people in days of yore were raised. Just because “they” turned out more or less okay from a “spare the rod, spoil the child” background, doesn’t mean that that kind of fear-based discipline was effective or humane. Brute force and coercion breeds underhandedness and cheating. Perhaps our current moment breeds a kind of free floating anxiety and inability to recover from small shocks. What’s the opposite of resilient?

Brian W. Thomas, Proctor Academy Head of School

Curated Listening:

With the passing of David Crosby from Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young makes me think about what we are teaching and what we are learning. Enjoy and listen to “Teach the Children Well.” Listen: HERE. Read the lyrics: HERE.