Each Proctor student graduates with a transcript filled with numbers and letters, a snapshot of their Proctor experience. While useful in some ways, this quick reference guide originally developed to standardize our assessment of a student’s “intelligence” for college admissions counselors insufficiently captures the entirety of a student’s growth journey through their high school years.

We have long known this at Proctor, and over the past year have begun to increasingly wrestle with what purpose grades serve in our educational model. What do grades do for us? What do they communicate? How do we use them? And, most importantly, are they a transparent measure of student growth or merely a convenient way to quantify a student’s current place in our class?

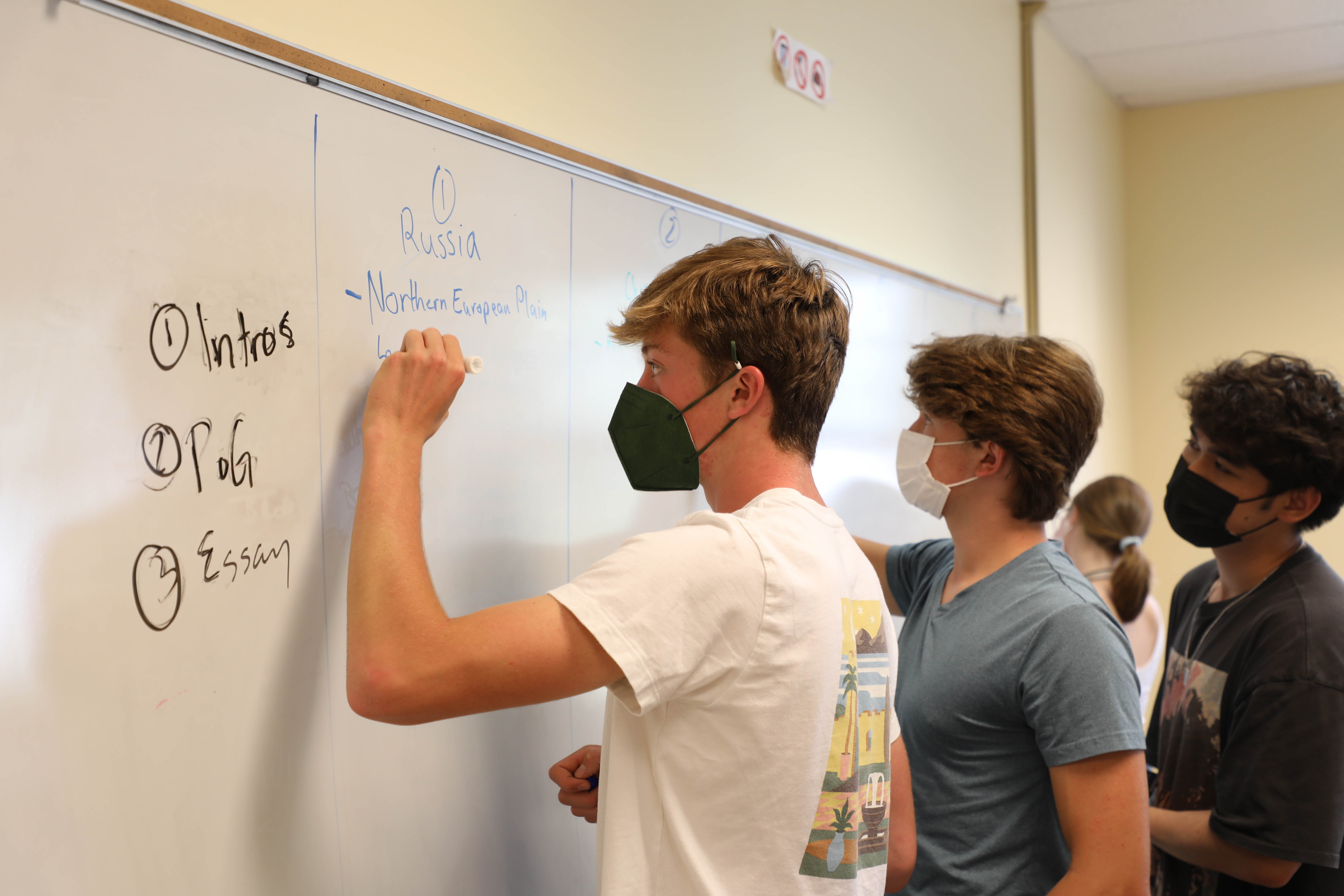

The relationships Proctor faculty build with students have always gone beyond the transactional. Faculty work to truly learn who is in their classroom - as humans, not just students - and to meet each individual where they are. These relationships, and the compassion that goes along with them, are constantly balanced with holding students accountable to the work necessary for growth. This is our challenge as educators: how do we help students understand both the work required for them to move forward on their learning journey, while providing them varied opportunities to demonstrate that learning within a supportive environment?

This summer we, as a faculty, read Grading for Equity by Joe Feldman. This book, like previous summer reads (Make it Stick, and The Art of Changing the Brain) has served as a catalyst for conversations about our practice as educators. In this case, we are looking critically at how we talk about grades and assessment with a goal of making grades a transparent reflection of student understanding - for the student, for the educator, for the parent/family, and for those who will teach the student in the future.

As we move from theoretical discussions and reading into action, we will work weekly in Teacher Learning Groups (TLGs) based on curricular areas to support one another as we experiment with new ways of communicating with students about their learning. From looking at rubrics and grading scales, to exploring how we use homework, our faculty are spending the Fall Term refining our practice, and sharing our learning with one another. As seasoned educators, we take this work very seriously. Any changes that we make to our teaching, assessment, and grading practices are made with the interest of the students in mind. We are confident that this work will continue to strengthen our educational model.

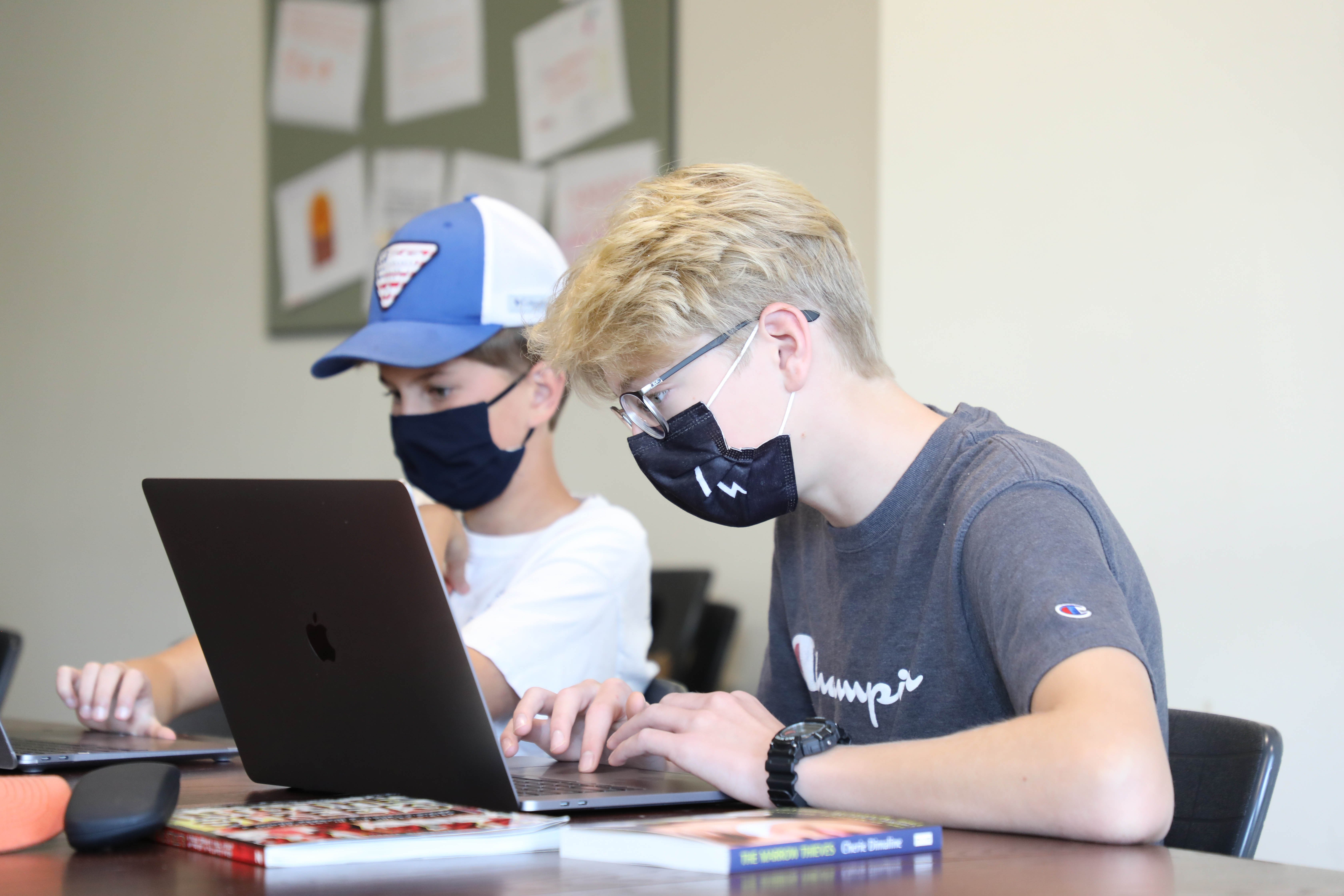

Students are seeing and experiencing this evolution in assessment first hand in each of their classes, but as parents, these shifts will feel different. The assessments your students will see this fall may be very different from how you were “graded” in high school. We believe this is a good thing. Institutionally, we are moving toward a place of allowing grades to serve as a clear, transparent reflection of student learning. Our students deserve this, and it is our responsibility to pursue this future.