Life at an academic institution synchronizes you to nature’s cycles as meteorological and calendar milestones create inseparable associations: fall foliage/Fall Family Weekend, first snow/Holderness Weekend, Thanksgiving Break/snow guns blowing at the Proctor Ski Area, frigid cold of January/pond hockey, late March snowstorms/Project Period, black flies/baseball season, and first thunderstorms of the spring/Graduation weekend. This winter, a disruption to this cycle occurred when Proctor made the decision to dredge the Proctor Pond in order to restore the aquatic ecosystem at the center of campus.

For the casual passersby, the steady stream of dump trucks and excavators down North Street and into the pond basin may be alarming, but for those within the community and those in tune with the ecological needs of the area, this evolution of the Proctor Pond is incredibly exciting. Throughout the past two years, collaboration among Proctor’s Environmental Coordinator Alan McIntyre, the late-Dave Pilla, State of New Hampshire permitting agencies, Proctor’s CFOO John Ferris, and Proctor’s AP Environmental Science students led to the decision to dredge the pond to a depth of 9-10 feet deep.

A glance through our digital archives (click HERE to see more) yields a powerful reminder of the evolution of the physical plant on which Proctor operates. In the late 1930s, the Proctor Pond was a mere bog in the center of campus that the Student Improvement Squad attempted to dam to create a skating/ice hockey surface.

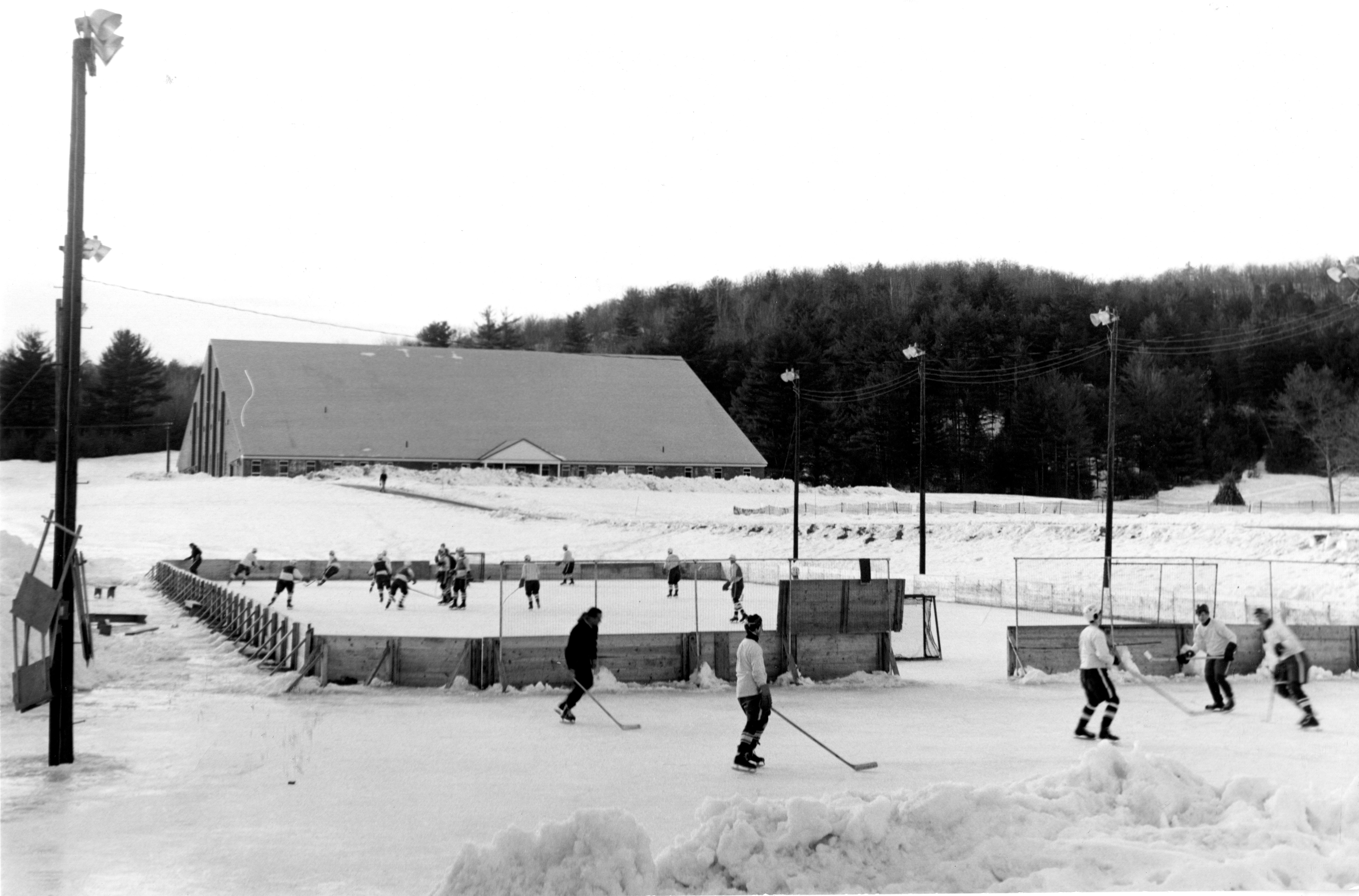

That first dam failed after a few short years, and in the mid-1950s, students and faculty created a more permanent dam structure that allowed Proctor to reinstate the sport of ice hockey under the leadership of Spence Wright.

Eventually lights were added to the seasonal “pond” as hockey grew into a popular winter sport for the all-boys school. Thankfully, most, but not all, winters allowed for a quick and hard freeze.

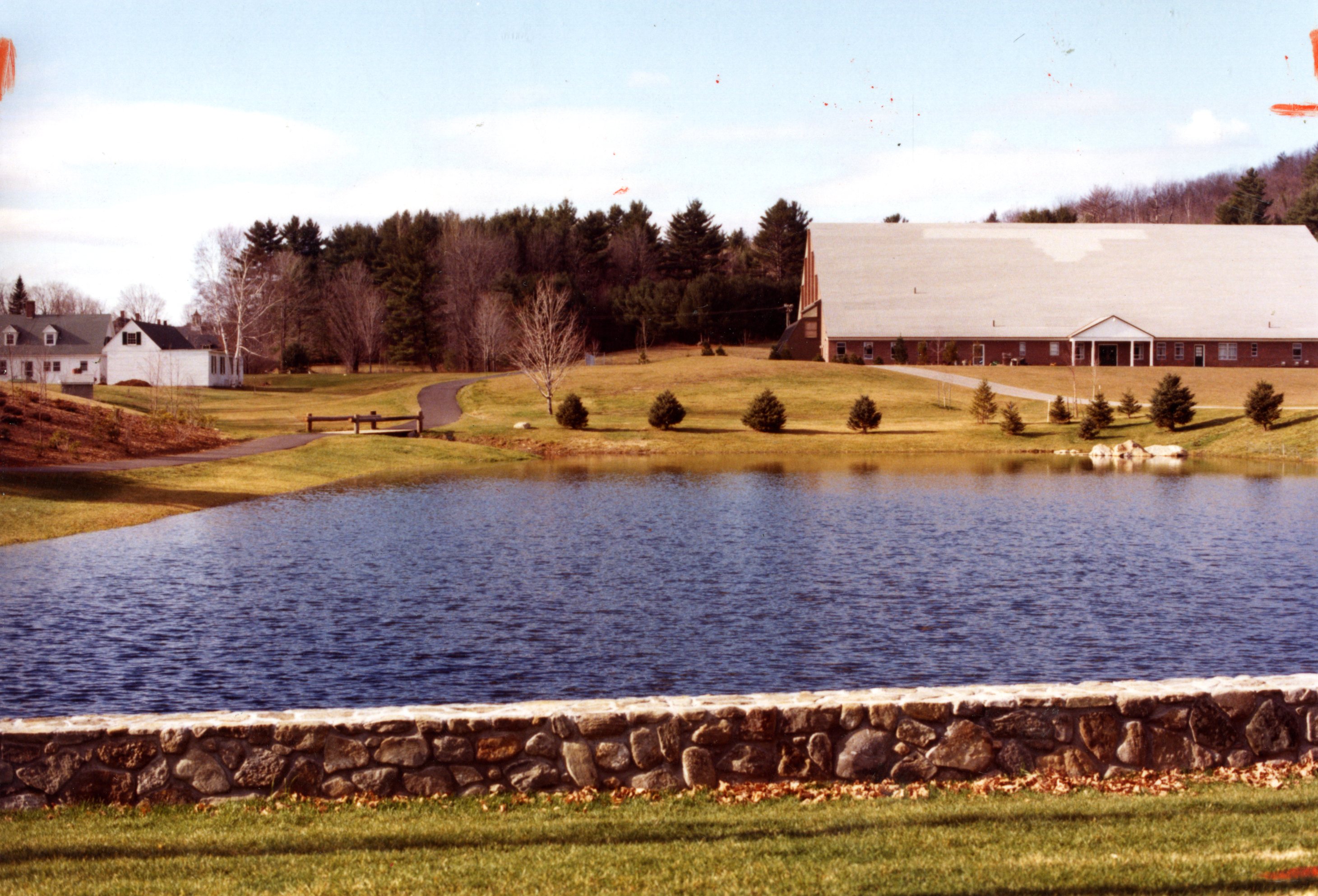

An artificial ice surface was built on the current site of the Teddy Maloney ‘88 Rink in 1974. At the same time, the stone wall damn at east end of the pond was erected, allowing the pond to fill into the campus feature it is today. Notice the lack of vegetation around the pond throughout the early 1980s.

Over the past forty years, those saplings have grown to surround the pond and to frame the Fowler Learning Center (built in 1995). As the pond evolved as an ecosystem of its own, so, too did the water quality, sediment, and aquatic flora and fauna that has since taken hold.

In 2007, AP Environmental Science teacher Alan McIntyre began what would become a ten-year longitudinal study of water temperature, water quality, and aquatic life inventory. The massive data set collected over the past decade helped inform the school’s decision to dredge the pond this year as students tracked shifts in pond health as turf fields were installed (2013) and the pond adjusted to a new campus drainage system. Among the variety data variables gathered was water turbidity, the cloudiness of the water. As Ben Charleston ‘19 shares in his analysis of pond health, “Turbidity often represents an increase in water quality and biodiversity, however, high levels of turbidity are not a good sign for the Proctor pond. Higher turbidity levels mean there is an excess amount of sediment entering the pond, which means the pond is slowly getting shallower.” We highly recommend you read the entirety of Ben's synthesis of the ten-year pond study HERE as his research and writing lay out the rationale for why a dredging project needed to take place.

Consultation with wildlife ecologists, state engineers, permitting agencies, and other experts in the field confirmed the long-term ecological benefits of dredging the pond to increase depth and to ‘reset’ the aquatic ecosystem. Lynn George of our Maintenance Team led the permitting process last summer, while her colleague Todd Goings has managed the project itself since it began in late December.

The dredging is still underway with an undetermined completion date later this winter depending on weather conditions. As spring eventually arrives, the pond will once again become a vibrant ecosystem, one that is home to a wider range of wildlife and plant life than the prior conditions were able to support. Next fall’s AP Environmental Science students will continue to study the pond’s health, and offer recommendations for future actions should their data suggest a need to change course. For now, the dredging and search for lost bikes (no, Liza ‘98, we have not yet found your ‘97 Kona Mountain Bike you lost in there…) will continue as we navigate another cycle of life here at Proctor.